Daisy Bates - Discussed by Nicolas Peterson

Daisy Bates - Discussed by Nicolas Peterson

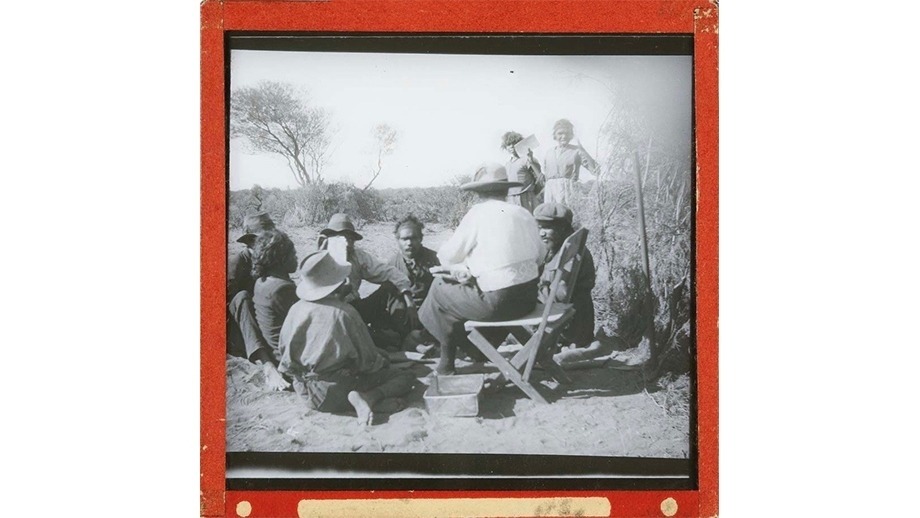

The red border first drew my attention to this slide that was housed with a large collection of others. The slides apparently belonged to an academic at the University of Adelaide and a number of them were labelled as from the west coast of South Australia. So the identification of the woman with her back to the camera as Daisy Bates makes sense as does the context, and the dress.

Daisy Bates was a woman of Irish background, a journalist, ethnographer, and welfare worker with a life long interest in Aboriginal culture. She is a well know Australian eccentric, especially because of her late Victorian dress which she wore to the end of her life, and her camp at Ooldea on the transcontinental railway line between Adelaide and Perth. There she carried out ethnographic research with the Aboriginal people drawn to this railway siding, and cared for them from 1919 to 1934, acquiring further fame because of visits by royalty on three occasions.

Although she had no formal anthropological background her training as a journalist made her a very good empirical observer whose records of Aboriginal life in Western Australia (Bates 1985) are especially important in the time of native title.

What initially drew me to the photograph was the man just left of centre whose face is obscured. On first viewing in poor light it looked as if somebody had scratched out the face, but had not done so in a particularly careful way. This suggested to me that may be the man had died since the photograph had been taken, and that in accordance with widely prevailing custom at the time, and out of respect for the dead, the identity of the dead person was obscured. I did wonder, however, at this level of sensibility by Europeans in the 1930s. This mistake underlines how easy it is in reading images to assimilate them to one’s preconceptions.

On closer inspection under better light it is clear that the man’s face is being obscured by the paper that the man second from the left is looking at. That he is looking at a paper is of interest in itself as it is unlikely that he could read and so it may have contained a photograph. But it is of interest that the woman standing at the back appears to be peering around a sheet of paper, in an ambivalent mix of curiosity about the photographer, at whom she is looking directly, and what may be possible concern about being photographed. Concerns among Aboriginal people at being photographed have been reported, although not widely (e.g. see Mulvaney et al 1997:348). If such was her concern, it raises the question of how she acquired her photographic literacy, especially in the case of the people at Ooldea who mainly came from the Musgrave Ranges, 450 km to the north, many with very little contact with Europeans before the establishment of Ernabella mission in 1937.

It is not known who took this photograph. However, Anthony Bolam, an employee of the Commonwealth railways posted to Ooldea in 1918, and who remaining there until 1925, by which time he had been station master for five years (South Australian Museum records AA 640), was a keen photographer and amateur natural historian. His immensely popular book, The Trans-Australian Wonderland (1923) was written while at Ooldea and includes two pictures of Daisy Bates with Aboriginal people. Bolam took a large number of photographs, now in the State Library of South Australia, in which Daisy features, but I have not been able to verify if this is one of his. Although Daisy was quite a private person she also needed and relished a certainly level of publicity and was clearly not averse to being photographed in certain situations. Here she appears to be holding one of her ethnographic ‘focus groups’. This photograph is quite like one taken on another occasion by Bolam (see Salter 1971: opposite page 108).

References

Bates, D. 1985. The native tribes of Western Australia (ed.) Isobel White. Canberra: National Library of Australia.

Bolam, A. G. 1923. The trans-Australian wonderland. Melbourne: McCubbin-James Press (Reprinted in 1924, 1925, 1927, 1930; facsimile in 1978).

Mulvaney, J., Morphy, H. and Petch, A. (eds.). My Dear Spencer: the letters of F.J. Gillen to Baldwin Spencer. Melbourne: Hyland House.

Salter, E. 1971. Daisy Bates: the Great White Queen of the Never Never. Sydney: Angus and Robertson