Franco-American Statue of Liberty - Discussed by Partner Investigator, Joe Kember

Franco-American Statue of Liberty - Discussed by Partner Investigator, Joe Kember

Having spent quite a bit of the last two years investigating slide series in museums throughout the UK, I have come to the conclusion that, by and large, my favourite slide sets are life model series. I especially love the staging of the models, which in large manufacturers like York and Son are often cleverly handled to express sentimental nuances that must have been important in the course of the show. In less expansive outfits, like T.T Wing’s small slide production facilities in Cambridgeshire, I also love the slides in which amateur models betray emotions that seem to belong outside the stated narrative of the series, and which suggest the labour of producing the slides (and I have written about this in an earlier ‘favourite slide’ article for the European ‘Million Pictures’ magic lantern project). Though life model gestures are clearly not what intrigues me about this image of the Statue of Liberty under construction, which formed part of a highly polished York and Son set dealing with the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1878, I like it for a very similar reason.

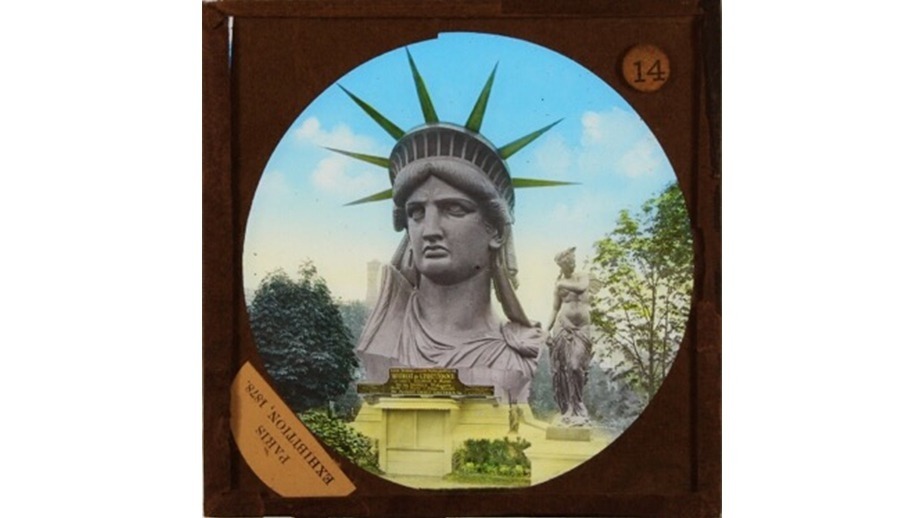

The slide was the fourteenth from a series of 54, and was most likely used accompanied by the script, also produced by York and Son in 1878. Lasting for a full seventeen sides of densely informative prose, the lecture suggests a solid 90 minutes of lecturing to audiences in Mechanics’ Institutes, schoolrooms, literary and scientific societies in the last decades of the nineteenth century, and a cursory survey of digitised British newspapers in 1878 indicates that this series’ topicality struck a chord among these types of users, since the lecture was delivered and reported upon several times. The description of the slide gives a sense of the typically austere tone:

“Gigantic Head of the Franco-American Statue of Liberty, something like the antique Colossus of Rhodes, destined to serve as a lighthouse for the harbour of New York. Proud and severe and yet sweet-looking, it is worthy of commemorating, as it does, the Declaration of American Independence. It is to be made of huge plates of copper, according to the designs of the celebrated sculptor, M. Bartholdi. A diminutive model of the statue, as it will be when finished, is exhibited close at hand. Liberty is standing, wrapped in the folds of an ample robe and in a most majestic attitude. Her left hand clasps the tablets of the Declaration of Independence, and her right hand raises high in the air a torch, with which she illumines the world.”

Besides reminding us of the fact that, until 1902, the statue also functioned, rather poorly, as a lighthouse in New York Harbour (a fact which surely muddied the metaphorical work Liberty performed), this slide and its reading are also striking for placing a familiar twentieth-century iconography into an alternative, and definitively French context. For the slide sequence, like the Exposition Universelle itself, emphasised the industrial feats of engineering that now permitted construction on such a grand scale, with the head of Bartholdi’s statue placed prominently outside the Exhibition’s Palace of Industry. First constructed and exhibited on French soil, Liberté consolidated themes of unity and modernity so important to the Republic at this time.

The hand-colouring of the slide – and of the full sequence – is also a source of pleasure. The precise attention paid to individual leaves, the artistic rendering of clouds on the glass, and the vibrant yellow of the sign have a curiously inverted effect, tending to attract the eye to the periphery of the image, especially to the seven greenish spikes of the crown, rather than to the untouched black and white sculpted face that occupies the centre. An apparently static image, with one clear point of interest, nonetheless encourages the eye to wander a little once colour is added, justifying for potential exhibitors the two-shilling price tag of the slide, as opposed to the one shilling black and white variant.

And yet, if the woman’s face remains only one point of interest on the coloured slide, a closer look reveals the influence of other women, since the colouring also speaks to the skill and craftsmanship of the labour undertaken by the mostly female labour force at York’s factory, in the small Somerset town of Bridgwater. This work is not without mistakes. Though most of the colouring seems accurate and effective, the miniature Statue of Liberty discussed within the slide description, immediately to the right of the giant head, is oddly occluded and easy to miss, the head and shoulders left grey like the giant head, but the body tinted yellow like the pedestal, the whole matching and fading into its background. By contrast, the larger statue pictured before the miniature is not identified within the lecture, though the absence of colour affords it the same visual status as Liberté, behind – highlighted and framed by the absence of colouring. This minor discordance between the rhetorics of slide and description is probably a simple error, and I imagine that a lecturer might have spotted or glossed over it, or perhaps even created a misleading impression of the full sized Liberté, based upon the semi-naked statue before it. However, as in the life model sequences I mentioned to begin with, what I really like here is the unintended suggestion of the labour that was involved in producing these slides. The little mistake, overpainting the miniature Liberté, reminds us of the intricate, repetitive labour of the painters, working on the tiny details in this slide before moving on to the next, and the next, and the next, following their own judgments about the pertinent details of the image without the benefit that visiting the exhibition might have afforded, and probably without the benefit of reading the lecture.