Extended Seminar: The Colour Revolution in Victorian Britain

Date & time

Location

Contacts

SHARE

Room 2.02, Sir Roland Wilson Building 120, McCoy Ave, ANU, and online via Zoom.

The ANU Centre for Art History and Art Theory is pleased to host this extended seminar on colour in Victorian Britain. Through presentations and discussion, we will examine colour in Victorian arts, sciences and discourse.

Please join us in person and online to hear papers by Matthew Winterbottom (Ashmolean Museum) and Keren Hammerschlag (ANU Centre for Art History and Art Theory), and presentations by early career researchers Madeline Hewitson (Ashmolean) and Sarah Hodge (ANU). These will be followed by an open discussion with the presenters and audience about the multiple facets of colour in Victorian Britain.

Light refreshments will be served during a mid-seminar break for those joining us on the campus. Make sure to book your ticket for catering purposes.

Those who can't attend in person can join via Zoom: https://anu.zoom.us/j/82864036397?pwd=N0hhMU9YRzUwRnBqaitHN3dIdHNhdz09; Password: 763609

About the Papers

Chromotope, The 19th Century Chromatic Turn

Matthew Winterbottom, Curator of Western Art Sculpture and Decorative Arts at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Matthew Winterbottom will speak about recent research relating to Chromotope, a European Research Council funded project which explores the Victorian ‘colour revolution’. A major exhibition on Victorian colour developed from Chromotope will open at the Ashmolean Museum in 2023.

Britain’s industrial supremacy during the Victorian era is often perceived through the darkening filter of coal pollution, and yet the industrial revolution transformed colour thanks to a number of innovations like the invention in 1856 of the first aniline dye. Colour thus became a major signifier of the modern, generating new discourses on its production and perception.

This Victorian ‘colour revolution’, which has never been approached from a cross-disciplinary perspective, came to prominence during the 1862 International Exhibition – a forgotten, and yet key, chromatic event which forced poets and artists like Ruskin, Morris and Burges to think anew about the materiality of colour. Rebelling against the bleakness of the industrial present, they invited their contemporaries to learn from the ‘sacred’ colours of the past – a ‘colour pedagogy’ which later shaped the European arts and crafts movement

Building on a pioneering methodology, and a multi-institutional partnership (Sorbonne Université and Oxford University, with the support of the CNAM), CHROMOTOPE therefore brings together literature, visual culture, the history of sciences and techniques and the chemistry of pigments and dyes, in order to offer new, invaluable insight into hitherto neglected aspects of 19th century European cultural history.

See more about Chromotope here: https://chromotope.eu/

The Problem of Colour in Victorian Art and Science

Keren Hammerschlag, Senior Lecturer, Centre for Art History and Art Theory, Australian National University

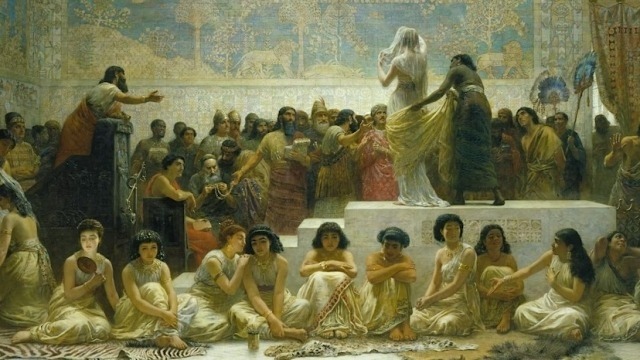

In this paper I consider the ways Edwin Long’s monumental painting Babylonian Marriage Market (1875; Royal Holloway, London) imagines race in the ancient world and, by extension, Victorian England. Babylonian Marriage Market was understood at the time of its first exhibition very much as an exercise in the depiction of ‘every shade of colour, from the firmness and fairness of Greek marble to Nubian bronze or black basalt,’ to quote The Times. Critics such as John Ruskin even went so far as to utilise anatomical and anthropological language in their descriptions of the work, highlighting the way the painting was understood in thoroughly scientific terms. The anthropological discourse that informed the production and reception of Babylonian Marriage Market sought to divide humanity into clearly defined categories based on skin, hair and eye colour. But even the most ardent Victorian race scientists, on occasion, admitted that colour was a particularly unreliable marker of racial difference (hence the preference for skulls). To overcome these drawbacks, anthropologists tried using all manner of instruments to identify skin colours, from spinning tops to colour charts. In Babylonian Marriage Market Long sought to organise the female figures lined-up along the base of the canvas according to racial hierarchies of the day, positioning the lightest-skinned maidens to the left of the canvas, and the darkest-skinned ones to the far right. However, there are aspects of the painting that resist an anthropological reading, revealing race to be malleable, elastic and a fundamentally unstable system of human categorization.

Journeys for Colour: Artist-Travellers and British Orientalism

Madeline Hewitson, Research Assistant for Chromotope: the 19th century Chromatic Turn, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

In the nineteenth century, the Middle East was a new and exciting destination to experience colour. Unsurprisingly, artists were at the forefront of this new wave of mass British tourism. They went in search of the opportunity to discern an altogether new understanding of the relationship between colour and light. Victorian artists approached the colours of the Orient with reverence and the receptiveness of a student willing to be taught. However, the idea of the alterity of Eastern colour, that it was somehow different to the colours of the West, implies the same divisive hierarchy Edward Said first identified in Orientalism (1978).

However, colour also offers, to use Mary Louise Pratt’s term, a contact zone, ‘a social space where disparate cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other’ or when inflecting this subject with the politics of colour Natasha Eaton’s notion of the ‘chromozone’. In this sense, colour could be an active agent that confronted and clinged to British artists’ palettes and canvases in transformative ways. As Frederic Leighton wrote as he watched a Damascene sunset, ‘It has dyed our spirits in colours that can never be washed out.’

This paper will closely read the work of several key British Orientalists to understand the role of colour in a selection of depictions of Egypt and the Holy Land. It will explore the way colour was used to convey Orientalist themes and how artists adapted the idea of a chromatic education in global and inter-imperial contexts.

The Colours of Fancy Dress: Hierarchy and Identity at Queen Victoria’s 1851 Bal Costumé

Sarah Hodge, HDR Candidate, ANU Centre for Art History and Art Theory

Within the sartorial world, colour can have powerful symbolic potential. This can be seen within the realms of fancy dress more specifically, at Queen Victoria’s 1851 costume ball. Victoria held three historically themed costume balls during the early years of her reign and they were an opportunity for members of the upper-class to dress in costumes inspired by the past. This paper analyses the descriptions and visual representations of costumes from Victoria’s final costume ball to explore the significance of colour in elite fancy dress. It examines how colour had the power to signal the hierarchy of guests but could also removed their ability to express more individualised symbols of identity.

Victoria’s 1851 ball was inspired by the Restoration or the seventeenth century. The important role played by colour is visually represented in Eugène Lami’s watercolour The Stuart Ball at Buckingham Palace, 13 June 1851 (1851, Royal Collection). The painting depicts the entrance of four quadrilles with coordinated costumes. These groups represent the “national quadrilles” inspired by costumes from England, France, Scotland and Spain. The colours and designs differ from the usual practice of guests wearing individualised costumes, inspired by specific figures from history. When seen together in the artwork, each group appears harmonious, wearing not only the same design but also the same colours. The uniformity of their costume colours emphasises the identification of the groups over the individuals and creates a cohesive ballroom scene.

About the Presenters

Matthew Winterbottom is Curator of Western Art Sculpture and Decorative Arts at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. His research interests cover a wide range of European decorative arts from the late medieval to the early twentieth centuries and he has extensive knowledge of metalwork, furniture, ceramics, glass and textiles and sculpture. He is committed to exploring ways of making this material more engaging and accessible to museum visitors. Matthew has over 25 years’ experience working with and researching European decorative arts. He has held curatorial roles at the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Royal Collection and the Holburne Museum in Bath. He joined the Department of Western Art in the Ashmolean Museum in March 2014 as Curator of Nineteenth-Century Decorative Arts where he was tasked with building a new collection of Nineteenth-Century decorative arts and redisplaying the Nineteenth-Century Art Galleries. Since January 2017, he has been responsible for the entire Western Art Sculpture and Decorative Arts Collections.

Keren Hammerschlag is Senior Lecturer in Art History and Curatorship in the Centre for Art History and Art Theory in the School of Art and Design at the ANU. Her research focuses on nineteenth-century British art and visual culture, and the many intersections and frictions between art and medicine during the Victorian and Edwardian periods. In 2015 she published her first monograph, Frederic Leighton: Death, Mortality, Resurrection (Ashgate). Most recently, she published an article on depictions of the so-called Jewish race in Victorian history painting in The Art Bulletin. Her current book project, The Chosen Race, considers the ways Victorian painters both affirmed and challenged racial boundaries through the creative use of pigment. In 2021 Hammerschlag was awarded a four-year ANU Futures Scheme Award to develop the Visual Medical Humanities at the ANU.

Madeline Hewitson is the research assistant for the ERC-funded project, Chromotope: the 19th century Chromatic Turn based at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford (UK). Her research on the theme of Victorian colour will be the subject of a major exhibition at the museum in September 2023. She was awarded a doctorate in History of Art at the University of York in 2020 for her thesis entitled ‘A Relief from Classicism: Frederic Leighton in the Near East, 1857-1895’. Her wider research focuses on Victorian visual culture across painting, sculpture and the decorative arts with a focus on British Orientalism.

Sarah Hodge is a third year doctoral candidate in the Centre for Art History and Art Theory at the Australian National University. Her work centres around the history of fancy dress and historically inspired fashion in Britain and France during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.